I had just put the finishing touches onto my fresco self portrait. As the plaster had already dried, I used secco (pigment and casein binder) to correct a few offending features and to add a tasteful floral cardigan. I was pleased with the result. It would be just the thing for the self portrait competition I was about to enter it for, the deadline for which was the very next day.

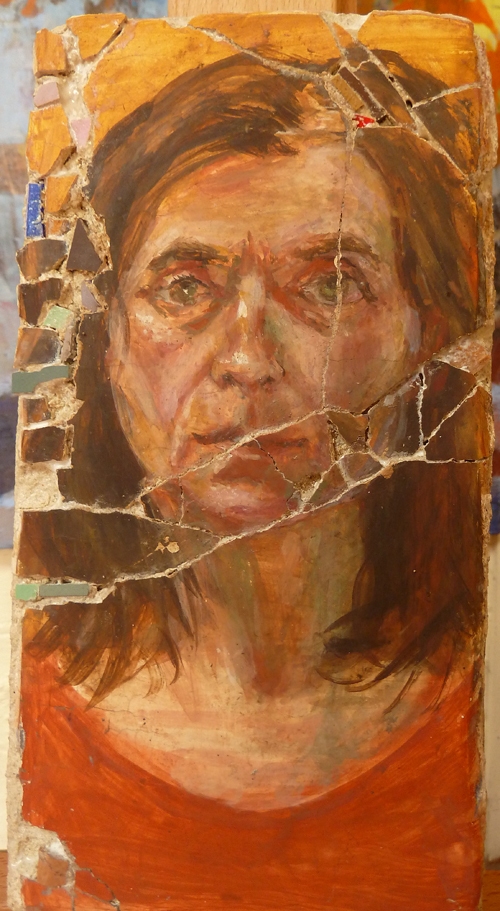

I needed to photograph it. As usual, I tried various exposures and distances. All was well. Then, I decided, for some reason I do not completely understand, to push the easel with the fresco back towards the wall. As I did so, the fresco came toppling down off the easel and landed with a smack on the floor. Like all these sorts of things, it happened in slow motion. I stared at it lying there with a chunk of the terracotta tile idling some inches away. I daren’t turn it over straight away, willing time into reversal. Eventually, I picked it up, cradling it in my hands, to find it was covered in cracks. I could perhaps live with that, but a few strategic bits of painted plaster had come away and one large area was threatening to detach itself.

How do you turn a disaster into something positive? It was clear I could not submit a fragile fresco to the competition- it would totally come apart in the post. I needed to secure it- somehow. For a while I had been investigating the technique of strappo– detaching the topmost layer from a fresco, but had also read about stacco, where a thicker layer of plaster is removed. As this was already happening, surely it would just be a matter of using trowels and spatulas to gently ease the layer off and then to stick it down on some wood.

I carefully lifted the entire bottom section of the fresco (mainly shoulders, neck and chin) and placed it on some paper towels. Now to work- the fresco was painted on a small tile, so there wouldn’t have to be much physical labour involved. I managed to lift some other areas (mainly the hair on one side) and, although it broke into small sections, they were stored in order on the paper towel. I was afraid to attack the actual face, which looked quite good isolated in the ruins of its surroundings. Perhaps I should have left it like that, as it was well attached and was refusing to budge.

I thought I had better practise on an area of hair on the other side, to see if I could successfully slide the spatula under the fast- set plaster. I tried, but it just crumbled away into a myriad of small brown splinters. Even the keenest jigsaw puzzler could not have rearranged them.

So, a change of plan was needed. I would stick the broken pieces back on to the terracotta tile and make a mosaic. At first I used PVA glue, but it had no effect. Then I remembered I had some cement adhesive left over from a mosaic workshop. This had a much greater binding strength. Thinking of mosaic led me to a box of glass and ceramic tesserae I had in my store cupboard. I could fill in some of the gaps with random bits. I didn’t have a tile cutter or nippers, so had to search around for bits that were roughly the right size. All the time, the clock was ticking. I had to get this done and I was determined to put it in for the competition.

I was enjoying the process and I liked how it was going. To be sure of stability, I decided to put a wash of PVA glue over the whole thing. This was my second mistake. It dissolved all the casein colours and left me with the original fresco marks- meaning a too small chin, plain orange T shirt and watery eyes. It has to be said, though, that the deep cracks and random bits of sparkle somewhat mitigated this. I would enter the portrait whatever- or else all this experimentation would be in vain.

To conclude, I did enter the fresco but it did not get chosen. Maybe it had nothing to do with the cracks or the too- small chin. Maybe it was just to do with the tiny chance of getting anything accepted to any competition. What did I learn from this? Two things- the casein binder is not waterproof and, in future, don’t move my easel unless the painting is secured.